[Image © warhistoryonline]

Editorial

In today’s polarised world, it is not uncommon to hear someone refer to someone else, whom they disagree with as a fascist, or a Nazi, or like Hitler. Hyperbole is alive and well on social media.

There is no question that the world of today is nothing like the world in the throes of global war, especially the latter part between 1942 and 1945.

But there were lessons to be learned from the political upheaval and violence of the twentieth century. Those like my parents, who were alive but children at that time, know the lessons well, but don’t speak of them much these days. Those like me, who were born in the years following The War learned the lessons by osmosis, from a society rebuilding after tearing itself apart and from uncles and family friends who witnessed the grisly, violent lessons with their own eyes.

What the generations since know of these lessons has been sanitised by time. Those who witnessed them in person are no longer with us and those who were children at the time, share happier memories with their grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

And yet, less than 100 years ago, fascism was very real. The continent of Europe was ruled by fascists. Indeed, it is within my own memory when the last remaining fascist leader, Franco of Spain, died in late 1975.

Fascists in Italy and Germany gained power through democratic elections. In Spain, Franco’s Nationalists won a bloody civil war against the left-leaning Republicans.

In the years following the armistice that ended World War One, Europe underwent a great political and social upheaval. War had weakened the hold on power enjoyed by the monarchies and the traditional elite and ruling classes of Europe. Disillusionment with the economic situation in the post first-war period drove a sense of disenchantment with the establishment. Communism had swept Russia and socialism gained increasing popularity with people throughout Europe.

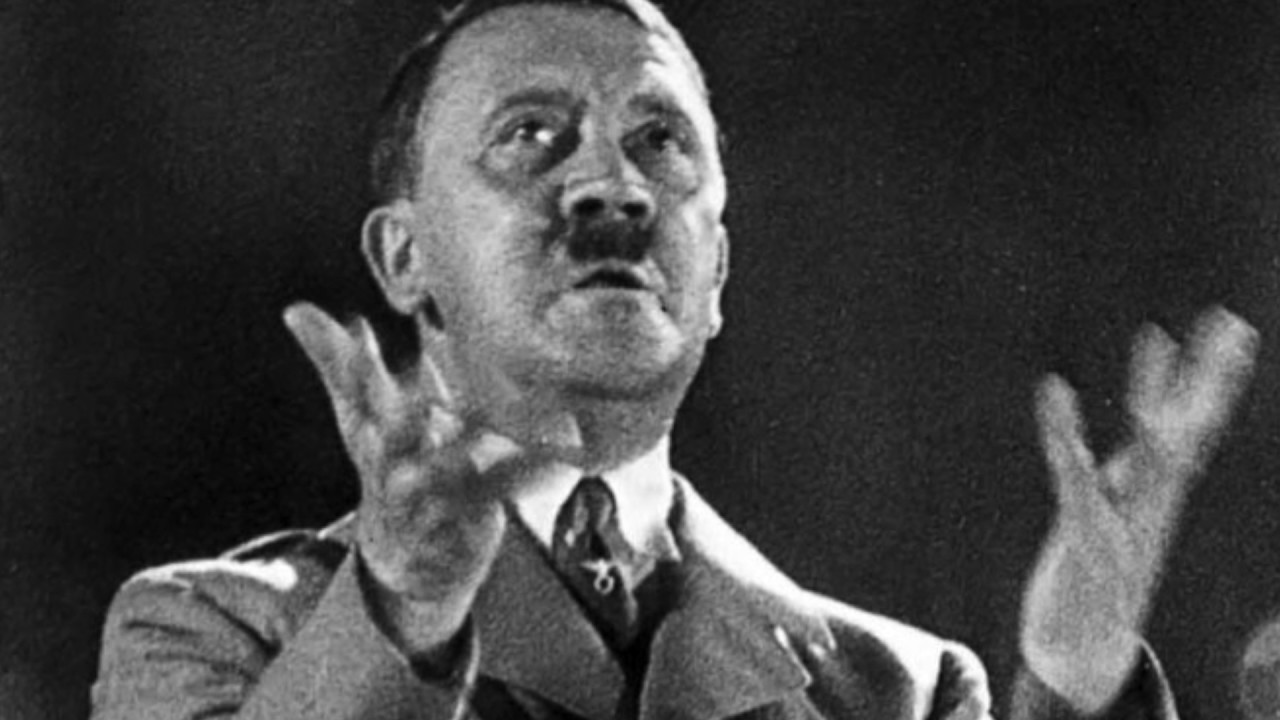

Fascist leaders, such as Mussolini in Italy, Hitler in Germany and Franco in Spain, offered a heady mix of socialism (or at least more centralised control of the economy) and nationalism, that promised to deliver a fairer share to the masses and pride in new, stronger, more glorious nations. An appealing prospect in the Europe of the early 1920s, riven by class, widespread unemployment and poverty.

Italy’s Benito Mussolini came to power first. In 1922 he became Prime Minister and leader of the National Fascist Party. He ruled democratically and constitutionally until 1925, then the threat of a communist revolution allowed Mussolini and the fascists to seize power, with little opposition, and turn Italy into a one-party totalitarian state, with Mussolini as dictator.

Meanwhile the situation in Germany was tumultuous. In the immediate post first-war period from 1918 to 1923 the country was wracked by hyperinflation and political extremism. Things settled greatly in the prosperous years between 1924 and 1929, but the collapse of the world’s economies in November 1929, which led to The Great Depression, hit Germany hard and precipitated the collapse of the German government in early 1930.

In the 1930 general election, the National Socialist Party won 6 million votes, making it the second largest political movement in Germany. President Paul von Hindenburg appointed a series of chancellors by emergency powers, until on 30 January 1933, he appointed Adolph Hitler, leader of the National Socialist Party, to the office of Chancellor.

Hitler moved quickly, using the Reichstag fire on 27 February 1933 to persuade von Hindenburg to enact the Reichstag Fire Decree, which abolished most German civil liberties including the rights to free speech, assembly, protest, and due process.

New elections on 5 March 1933 gave the nationalist parties, including the National Socialists dominance of the parliament and on 23 March 1933, it passed The Enabling Act, which gave the cabinet and the chancellor the power to make and enforce laws, without the involvement of the Reichstag or the president.

When Hindenburg died in 1934, Hitler solidified his position as absolute dictator of Germany, under the title of Fuhrer or Leader.

In Spain, a failed military coup in July 1936 sparked the Spanish Civil War. Between 1936 and 1939, the Spanish fought between, in simplistic terms, leftist Republicans aided by the Soviets and right-leaning Nationalists, supported by fascist Italy and Germany.

Francisco Franco commanded Spain’s African colonial army. During the war, he became leader of his nationalist faction and was appointed Generalissimo and Head of State in 1936. By consolidating all nationalist parties, he created a one-party state.

When the nationalists declared victory in 1939, Franco’s dictatorship was extended by political repression and the use of forced labour, concentration camps and executions.

All these events, in Italy, in Germany and in Spain, occurred before the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939.

Five short years later, Europe, the cradle of The Enlightenment, powerhouse of science, centre of Christendom, the heart of western civilisation, was reduced to a smoking ruin. Ruin on a continental scale and an estimated 70 – 85 million people had lost their lives.

All this happened within the lifetimes of our parents and grandparents. Fascists in Europe didn’t gain their power through divine providence, but through democratic support and popular uprising. The people of Europe handed the fascists their power willingly.

If you take nothing more from this essay, take that one fact.

When we are willing to forgo democracy, freedom and liberty; when we are prepared to sacrifice speech and association for comfort and conformity, we are paving our own road to hell.

If we believe it can’t happen today; it already has, within the lifetimes of my mother and father.

And if we look at the world around us today and believe it can’t happen again, then we have failed to learn the grisly and violent lessons of the twentieth century.

Published 26 January 2022

By Colin Ford